The water gas shift (WGS) reaction represents one of the foundational industrial catalytic processes for hydrogen production and syngas adjustment, converting carbon monoxide and water vapor into carbon dioxide and hydrogen according to the equilibrium equation:

CO + H2O ⇔ CO2 + H2

History

Italian physicist Felice Fontana discovered the water gas shift reaction in 1780, though its industrial significance remained unrecognized for over a century.

Before the early 20th century, hydrogen production relied on reacting high-pressure steam with iron to generate iron oxide and hydrogen, an expensive and inefficient process. The development of the Haber-Bosch ammonia synthesis process created urgent demand for large-scale, economical hydrogen production, driving recognition of the WGS reaction's industrial value.

BASF researchers initiated intensive development work in the early 1910s to optimize the process for ammonia synthesis applications. The challenge was removing carbon monoxide from coal gasification products, as CO would poison the iron-based ammonia synthesis catalyst. They developed the first commercial heterogeneous catalyst system based on iron oxide-chromium oxide (Fe2O3-Cr2O3), designated the high-temperature (HT) shift catalyst, which operated above 400°C and reduced CO levels to 2-4% at reactor outlets.

The early 1960s brought a major advancement with copper-zinc oxide (Cu-ZnO) catalysts, termed low-temperature (LT) shift catalysts, which operated at approximately 200°C and achieved exit CO concentrations of 0.1-0.3%. This improvement reflected better exploitation of favorable thermodynamic equilibrium at lower temperatures.

Technology Summary and Chemistry

The WGS reaction is moderately exothermic with a standard enthalpy change of -41.2 kJ/mol at 298 K and a Gibbs free energy of -28.6 kJ/mol:

- According to the Van't Hoff equation, the equilibrium constant decreases with increasing temperature, making hydrogen production thermodynamically more favorable at lower temperatures.

- However, reaction kinetics improve with increasing temperature, creating the fundamental tension between thermodynamic conversion and kinetic rate that shapes industrial reactor design.

The reaction mechanism depends critically on catalyst composition and operating temperature. Two primary mechanistic pathways have been established through extensive research:

- The redox (regenerative) mechanism dominates in high-temperature applications over iron-chromia catalysts above 350°C. In this pathway, carbon monoxide is oxidized by lattice oxygen from the catalyst surface to form CO2, creating an oxygen vacancy. Water then undergoes dissociative adsorption at this vacancy site, yielding two hydroxyl groups. These hydroxyls disproportionate to regenerate the catalytic surface and release hydrogen.

- The associative Langmuir-Hinshelwood mechanism predominates at lower temperatures on metal-oxide-supported transition metal catalysts. Water dissociates on the catalyst surface to produce adsorbed hydroxyl and hydrogen species. The dissociated water reacts with adsorbed CO to form an intermediate—either a carboxyl or formate species. Recent experimental studies confirm that the carboxyl pathway accounts for approximately 90% of the total reaction rate due to the thermodynamic stability of surface intermediates. The carboxyl intermediate subsequently dehydrogenates to yield CO2 and adsorbed hydrogen atoms, which recombine to form molecular hydrogen.

Catalyst Systems

High-temperature shift catalysts typically contain 74.2% Fe2O3, 10.0% Cr2O3, and 0.2% MgO. Chromium functions as a structural promoter, stabilizing the iron oxide phase and preventing sintering at elevated temperatures. During operation, the bulk hematite (α-Fe2O3) phase transforms to magnetite (Fe3O4), which constitutes the catalytically active bulk phase under reaction conditions.

Low-temperature shift catalysts employ compositions of 32-33% CuO, 34-53% ZnO, and 15-33% Al2O3. Copper oxide serves as the active catalytic species, zinc oxide provides structural support and sulfur tolerance, while alumina prevents copper dispersion and pellet shrinkage.

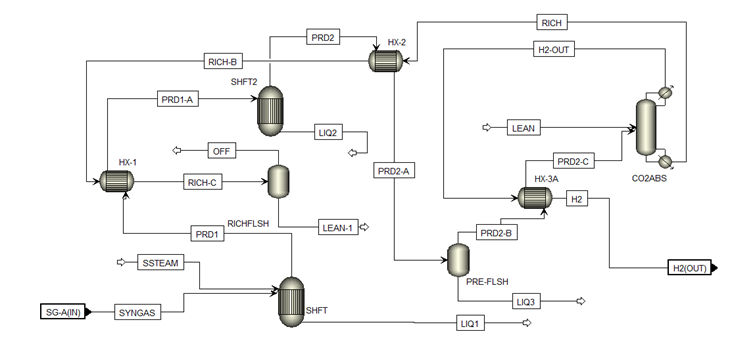

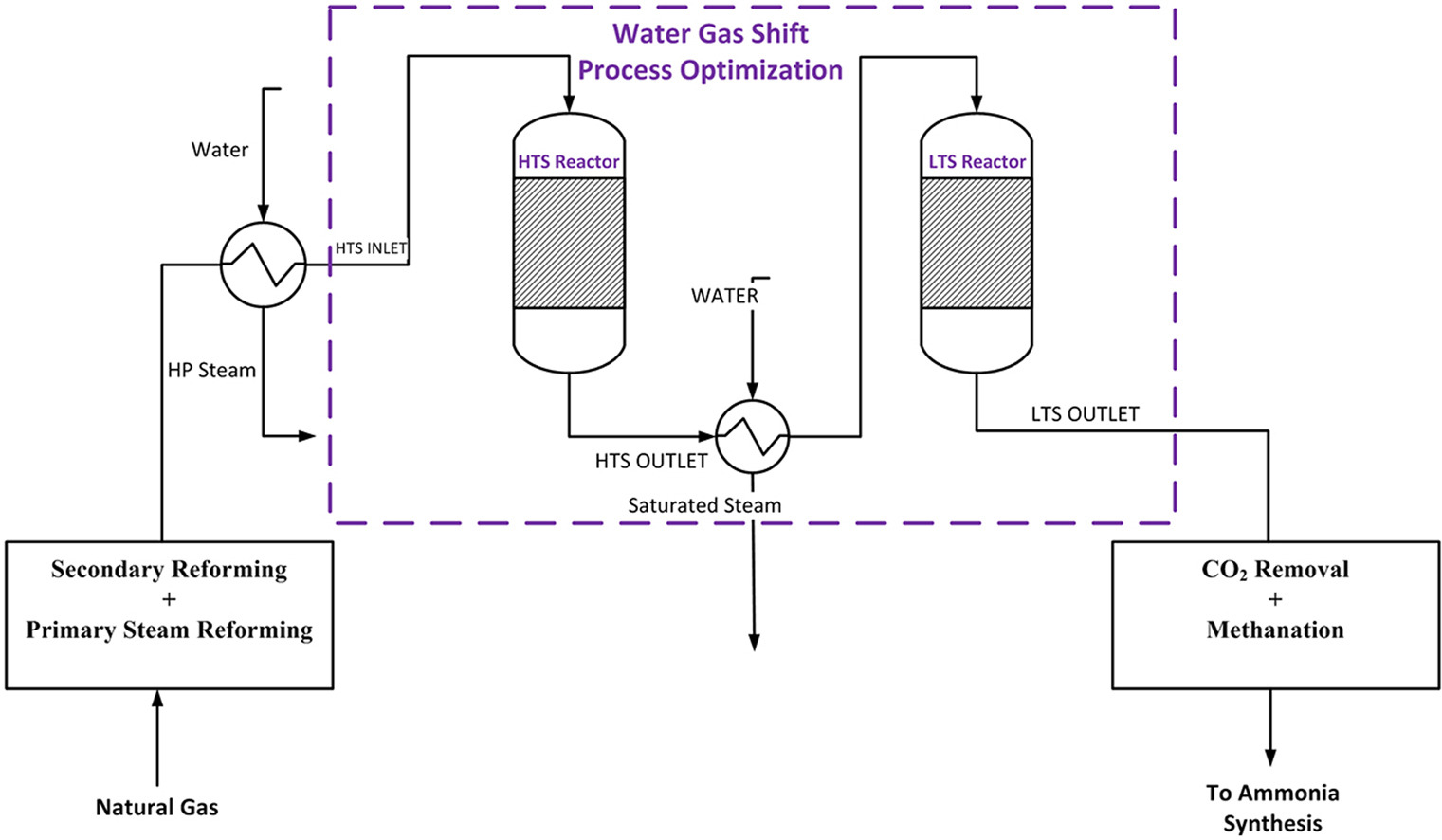

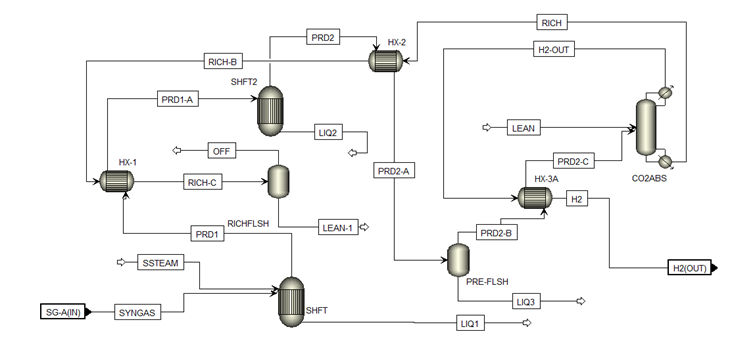

Detailed Process Description

Industrial water gas shift processes employ a two-stage configuration to exploit both favorable kinetics at high temperature and favorable thermodynamics at low temperature. This dual-reactor approach with interstage cooling represents the standard industrial design for maximizing overall CO conversion while managing the exothermic heat release.

Water gas shift flowsheet [2]

- The high-temperature shift (HTS) reactor receives syngas from upstream reforming or gasification units, typically containing 8-12% CO on a dry basis. The HTS operates within a temperature range of 310-450°C, with inlet temperatures maintained at approximately 350°C. The exothermic reaction generates temperature increases of 50-110°C along the reactor length, depending on CO conversion achieved. To prevent exit temperatures from exceeding 550°C, which would damage the catalyst, inlet temperature control is critical. Industrial HTS reactors operate across a pressure range from atmospheric to 82.7 bar depending on the application.

- Process gas exiting the HTS reactor passes through heat recovery equipment to preheat natural gas feedstock, boiler feedwater, and demineralized water for steam generation in integrated systems. The gas then undergoes cooling to approximately 200-250°C before entering the low-temperature shift (LTS) reactor. This interstage cooling is essential to shift thermodynamic equilibrium toward higher hydrogen yields in the second stage.

- The LTS reactor completes CO conversion, typically reducing outlet concentrations to below 1% and often to 0.1-0.3%. Copper-based catalysts in the LTS are more susceptible to poisoning, particularly by sulfur compounds, necessitating upstream guard beds for sulfur removal. The upper temperature limit of 250°C prevents thermal sintering of copper crystallites, which would cause irreversible catalyst deactivation. Following LTS, the raw hydrogen stream undergoes further cooling to approximately 40°C in air coolers and trim coolers, with acid process condensate separation before final purification, typically via pressure swing adsorption.

Important operational constraints include maintaining appropriate H2O/CO ratios, as low ratios can trigger undesired side reactions including metallic iron formation, methanation, carbon deposition, and Fischer-Tropsch reactions. Steam-to-carbon ratios typically range from 2.5 to 4.0 depending on catalyst formulation and operating conditions.

Process Efficiency

The efficiency of water gas shift reactors depends on multiple interrelated parameters including temperature, pressure, process configuration, space velocity, steam-to-gas ratio, and catalyst activity.

- Temperature influence: The moderately exothermic nature of the reaction (ΔH° = -41.2 kJ/mol) means that equilibrium conversion decreases with increasing temperature according to Le Chatelier's principle. Over the temperature range of 600-2000 K, the equilibrium constant can be described by established correlations.

- Pressure influence: Because the reaction proceeds with no change in the number of moles (one mole of reactants yields one mole of products), pressure has no thermodynamic effect on equilibrium position. However, pressure influences mass transfer rates and catalyst effectiveness factors in industrial reactors.

- Process configuration effect: The two-stage configuration with HTS and LTS reactors allows overall CO conversions exceeding 98%, with exit CO concentrations routinely below 0.3%.Single-stage HTS reactors typically achieve 85-92% CO conversion, with exit concentrations of 2-4% CO; addition of the LTS stage pushes conversion to 98-99.5%.

- Space velocity: Gas hourly space velocities (GHSV) in industrial units typically range from 2,000 to 15,000 h-1 depending on catalyst activity and required conversion. Higher space velocities reduce capital costs but may compromise conversion, while lower space velocities increase reactor volume and catalyst inventory.

- Steam-to-Gas ratio influence: Steam-to-gas ratio significantly influences conversion and catalyst stability. Excess steam shifts equilibrium toward product formation and helps prevent carbon deposition and catalyst reduction, but increases energy consumption for steam generation. Typical industrial practice maintains steam ratios of 3:1 to 4:1 on a molar basis relative to CO content, balancing conversion efficiency against operating costs.

Use Cases

The WGS reaction serves as an integral component in multiple major industrial processes for hydrogen production and syngas conditioning.

- Steam Methane Reforming: Its most prevalent application occurs downstream of steam methane reforming (SMR) in hydrogen plants. Steam reforming generates syngas with H2/CO ratios of approximately 3:1, but significant CO content remains (8-12% dry basis). The WGS reaction converts this CO to additional hydrogen while simultaneously reducing CO to trace levels required for downstream applications.

- Ammonia Synthesis: In ammonia synthesis via the Haber-Bosch process, the WGS reaction is essential for producing high-purity hydrogen from coal gasification or steam reforming. Carbon monoxide acts as a severe poison to iron-based ammonia synthesis catalysts, necessitating reduction to parts-per-million levels. The two-stage WGS configuration, often followed by methanation or pressure swing adsorption, achieves the required purity specifications.

- Fischer-Tropsch synthesis: FT for producing liquid hydrocarbons requires precise H2/CO ratios typically ranging from 1.5:1 to 2.3:1 depending on the catalyst system and target products. The WGS reaction provides flexible adjustment of syngas composition, allowing optimization for specific catalyst requirements and product slates.

- Methanol synthesis similarly requires H2/CO ratio adjustment to approximately 2:1, with the WGS reaction providing the necessary tuning capability.

- Full Cells: When hydrogen is produced from hydrocarbon fuels (like natural gas or gasoline) for use in fuel cells, the reforming process generates a gas mixture containing both hydrogen and carbon monoxide. PEM fuel cells require very pure hydrogen because even small amounts of CO (above 100 ppm) poison the platinum catalysts in the fuel cell electrodes, causing the fuel cell to stop functioning. The WGS reaction serves a dual function: increasing hydrogen yield from hydrocarbon fuels while reducing CO concentrations that would poison platinum electrocatalysts.

References

- Janbarari S. R., Taheri Najafabadi, A.. Simulation and optimization of water gas shift process in ammonia plant: Maximizing CO conversion and controlling methanol byproduct. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, 48(64), 25158–25170. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2022.12.355

- Olanrewaju F., Oboh I., Adesina O., Anyanwu C. & Ewim, D. Modelling and simulation of hydrogen production plant for minimum carbon dioxide emission (Feb 15, 2023). The Journal of Engineering and Exact Sciences, 9(1), 15394. DOI: 10.18540/jcecvl9iss1pp15394-01e

- Wikipedia. Water-gas shift reaction (page version: Jan 14, 2026)

- Ambrosi A., Denmark S.E.. Harnessing the Power of the Water-Gas Shift Reaction for Organic Synthesis (Sep 6, 2016). Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 55(40):12164-89. DOI: 10.1002/anie.201601803. Epub 2016 Sep 6. PMID: 27595612; PMCID: PMC6201252.

- Department of Energy (DOE), National Energy Technology Laboratory. 6.2.6. Water Gas Shift & Hydrogen Production

- Yalcin O., Sourav S., Wachs, I. E.. Design of Cr-Free Promoted Copper–Iron Oxide-Based High-Temperature Water−Gas Shift Catalysts (Sep 14,2023). ACS Catal. 2023, 13 (19), 12681–12691. https://doi.org/10.1021/acscatal.3c02474

- ScienceDirect. Water-Gas Shift

- Ladebeck, J. R., and J. P. Wagner. Catalyst Development for Water-Gas Shift. Handbook of Fuel Cells – Fundamentals, Technology and Applications, edited by Wolf Vielstich et al., vol. 3, part 2, John Wiley & Sons, 2003, pp. 190–201.

- Brightling J.. Technical Report 1722JM/0119/0/ENR: Improvements to water gas shift process (2019). Johnson Matthey

- Chen J.P. et al.. World patent WO2020236381A1: Chromium-free, iron-based catalyst for water gas shift reaction and methods of use thereof (Apr 22, 2020: Priority date). Application filed by RTI International Inc

- Castro-Dominguez B. et al.. Integration of Methane Steam Reforming and Water Gas Shift Reaction in a Pd/Au/Pd-Based Catalytic Membrane Reactor for Process Intensification (Sep 19, 2016). Membranes (Basel). 6(3):44. DOI: 10.3390/membranes6030044. PMID: 27657143; PMCID: PMC5041035.

- ScienceDirect. WaterGas Shift Reaction

- Ramírez Reina, T., et al.. Twenty Years of Golden Future in the Water Gas Shift Reaction (Aug 20, 2014). Heterogeneous Gold Catalysts and Catalysis, edited by Zhen Ma and Sheng Dai, Royal Society of Chemistry, 111–39.

- Grabow, Lars C., et al.. Mechanism of the Water Gas Shift Reaction on Pt: First Principles, Experiments, and Microkinetic Modeling (Mar 5, 2008). The Journal of Physical Chemistry C, 112(12), 4608–17. American Chemical Society. DOI: 10.1021/jp7099702

- Kalamaras, C. M. et al.. Effects of reaction temperature and support composition on the mechanism of water–gas shift reaction over supported-Pt catalysts (May 20, 2011). The Journal of Physical Chemistry C, 115(23), 11595–11610. DOI: 10.1021/jp201773a

- Zhang, Q. et al.. CO2 Conversion via Reverse Water Gas Shift Reaction Using Fully Selective Mo–P Multicomponent Catalysts (Apr 19, 2022). Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research, 61(34), 12857–12865. DOI: 10.1021/acs.iecr.2c00305

- Polo-Garzón, F. et al.. Elucidation of the reaction mechanism for high-temperature water gas shift over an industrial-type copper–chromium–iron oxide catalyst (Apr 25, 2019). Journal of the American Chemical Society, 141(19), 7990–7999. DOI: 10.1021/jacs.9b03516

- Dehimi, L. et al.. Hydrogen production by the water-gas shift reaction: A comprehensive review on catalysts, kinetics, and reaction mechanism. Fuel Processing Technology, 267, 108163. DOI: 10.1016/j.fuproc.2024.108163

- Agi, D. T. et al.. Techno-economic Analysis and Optimization of Water-Gas Shift Membrane Reactors for Blue Hydrogen Production (Aug 27, 2024, preprint). ChemRxiv. DOI: 10.26434/chemrxiv-2024-9cjzc-v3

- Klaehn, John, et al.. Water-Gas-Shift Membrane Reactor for High-Pressure Hydrogen Production: A Comprehensive Project Report (FY 2010 – FY 2012) (Jan. 2013). INL/EXT-12-27377, Idaho National Laboratory

- Eddi I., Chibane L.. Parametric study of high temperature water gas shift reaction for hydrogen production in an adiabatic packed bed membrane reactor. Rev. Roum. Chim., 65(2), 149-164. DOI: 10.33224/rrch.2020.65.2.04

- Francesconi, J., Mussati, M., & Aguirre, P.. Analysis of design variables for water-gas-shift reactors by model-based optimization. Journal of Power Sources, 173(2), 467–477. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpowsour.2007.04.048