UK North Sea Exploration at Historic Standstill: Policy-Driven Divergence from Norway

Article Image: Offshore Drilling Rig on the Sea

The End of Synchronized Decline

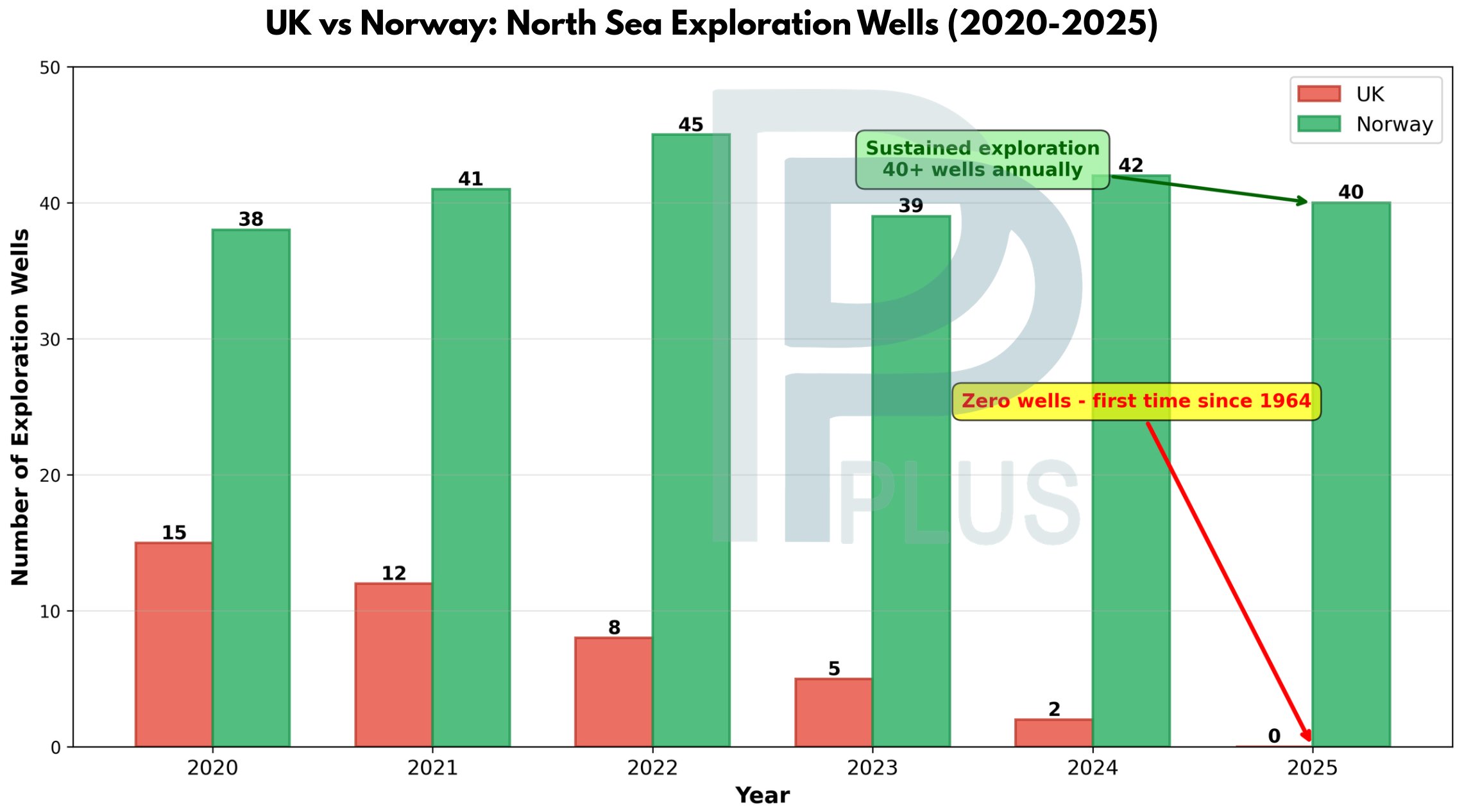

The North Sea oil provinces of the UK and Norway both peaked in the late 1990s at approximately 6 million barrels per day—mbpd (approximately 300 million tonnes of oil equivalent—mtoe) combined and entered synchronized decline through the 2000s and 2010s. However, this historical pattern has been decisively broken since 2023. While the UK accelerates its production decline, Norway has reversed its trajectory: Norwegian oil production surged to 1.96 mbpd in July 2025—a 10-year high—driven by seven major new field developments including the Johan Castberg field that began production

in March 2025. Norway's 2025 combined oil and gas production is forecast at 4.2 million barrels of oil equivalent per day (approximately 572 mtoe), representing 3% growth, while UK production continues its steepest decline in decades. Norway's thriving petroleum sector continues feeding its Government Pension Fund—now exceeding 11.5 trillion NOK—ensuring intergenerational wealth accumulation even as the UK struggles with mounting fiscal deficits.

Figure 1 - Source: see closing note

Fiscal and Regulatory Drivers of Divergence

The contrasting trajectories stem from fundamentally different policy approaches.

The UK's exploration halt results from the Energy Profits Levy raised to 78% on upstream profits and Energy Secretary Ed Miliband's ban on new exploratory licenses in untapped areas. While drilling continues in pre-licensed areas, investor sentiment has reached "all-time low" according to Westwood Global Energy, driven by fiscal uncertainty and regulatory hostility. The government's November 2025 North Sea Strategy provides minimal relief, introducing "Transitional Energy Certificates" for extraction near existing fields while maintaining the exploration ban. The October 2024 Autumn Budget delivered further punishment to the sector with massive tax increases as the Starmer Government attempts to tax its way out of an exploding budget deficit, ignoring warnings from industry that punitive taxation accelerates capital flight rather than revenue growth.

Norway's contrasting approach includes a supportive fiscal regime with record investment of 274.8 billion NOK ($27 billion) in 2025, vigorous exploration activity with 40 wells drilled, and strategic long-term planning buffered by its sovereign wealth fund of 11.5 trillion NOK. Despite Norway's headline tax rates appearing high, the effective fiscal burden and regulatory certainty incentivize continued investment. Norway's offshore directorate actively encourages exploration and has approved multiple new field developments extending production horizons through 2050 and beyond.

While the UK government squeezes its remaining producers, Norway awarded 53 new exploration licenses in 2024 alone, demonstrating the divergence between wealth creation and wealth destruction approaches to resource management.

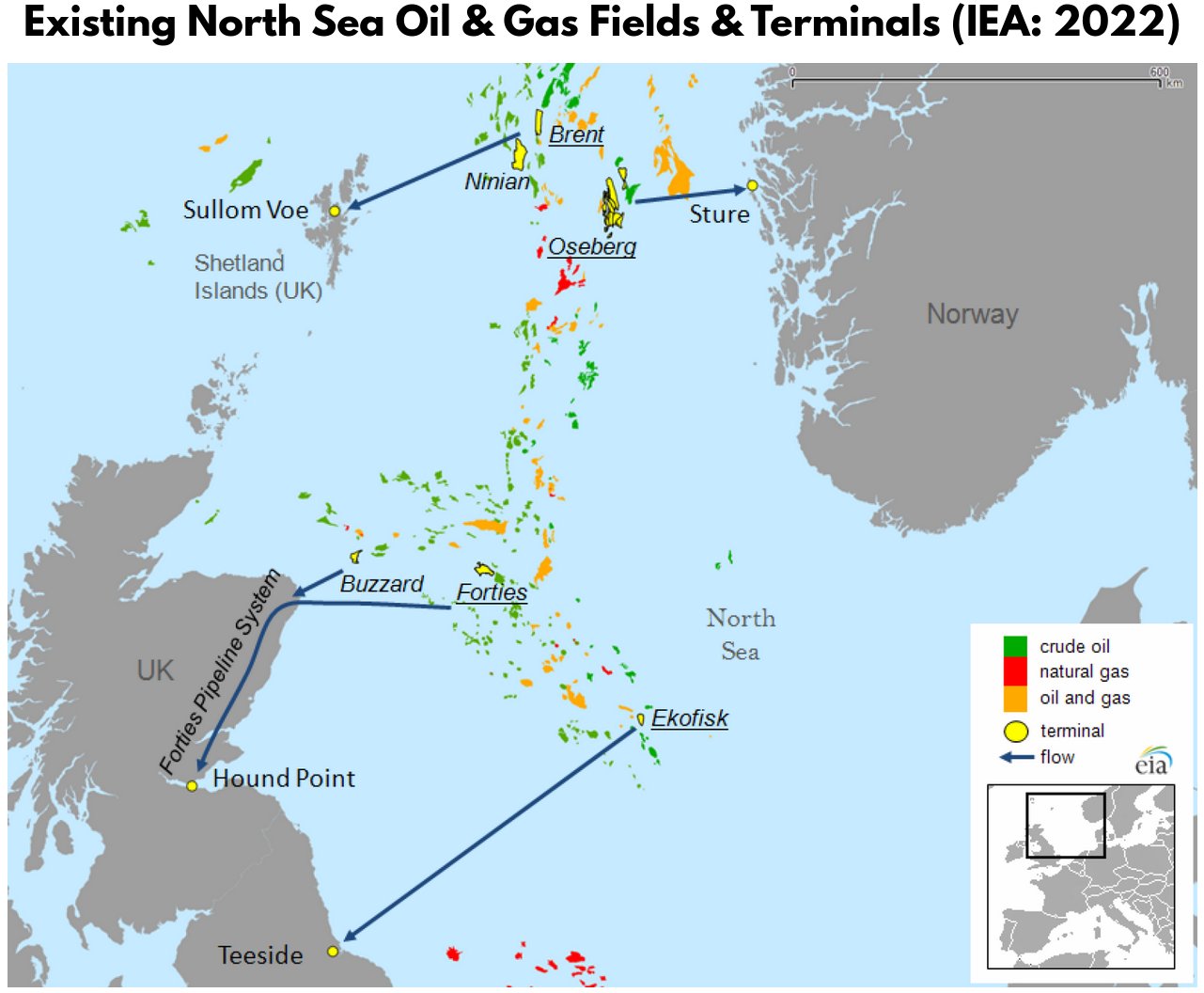

Figure 2 - via Society of Petroleum Engineers (May 27, 2022)

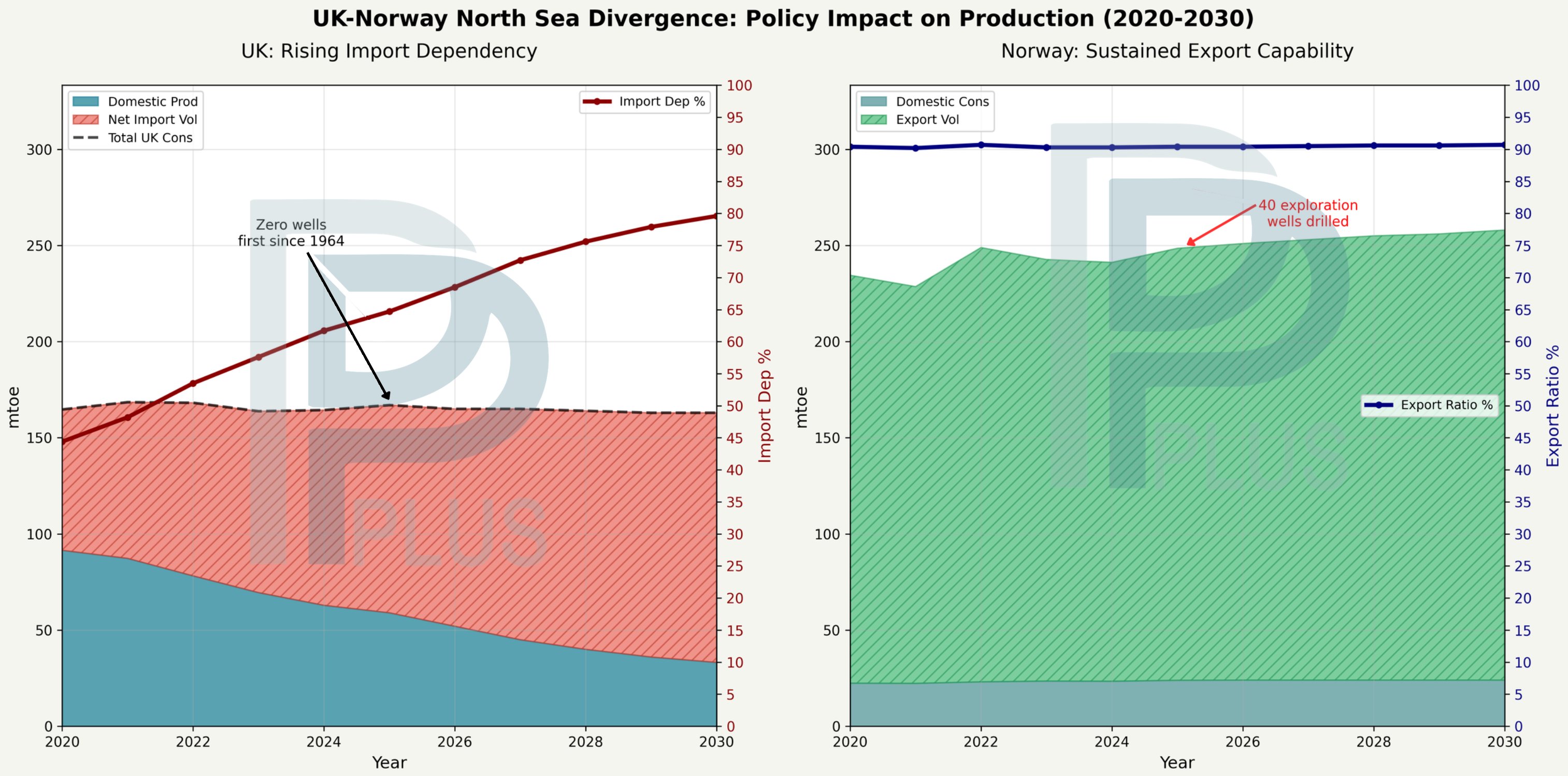

Production Decline and Import Dependency

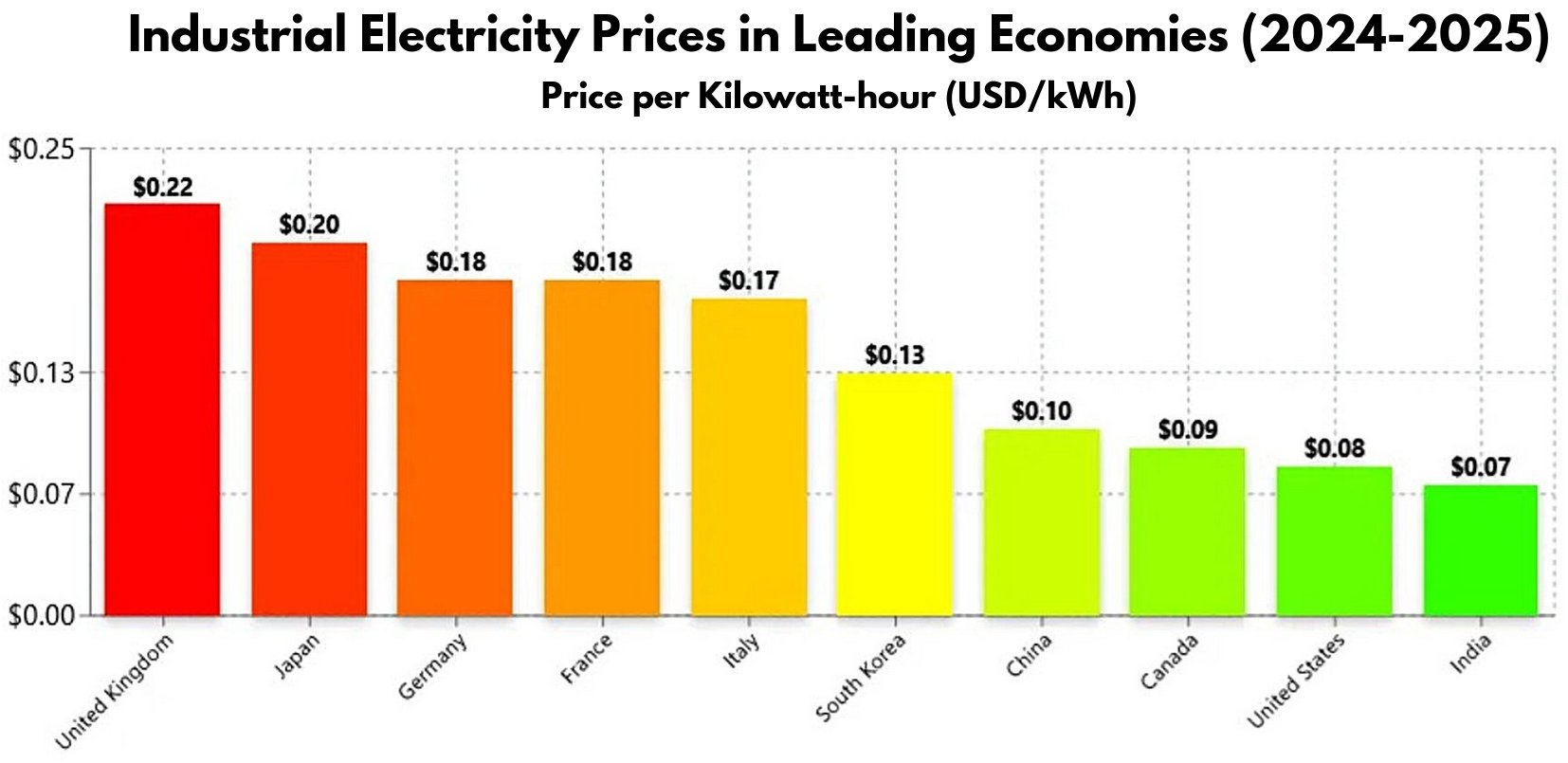

UK oil production declined 8.8% in 2024 to 33.3 million tonnes oil equivalent—the lowest since 1976—while gas production fell 10.3% to 29.6 mtoe, the lowest since 1973. Total oil and gas production reached just 62.9 mtoe in 2024, down from 91.5 mtoe in 2020. Import reliance escalated in parallel: net imports reached 101.5 mtoe in 2024, representing 61.7% import dependency, up from 94.3 mtoe (57.6%) in 2023. Net oil imports reached 24.3 billion pounds in monetary value, the highest deficit on record. Gas import dependency rose to 49% in 2024, with Norway ironically supplying 76% of UK gas imports. UK oil and gas revenues fell from £6.1 billion in 2023-24 to £4.5 billion in 2024-25, with Energy Profits Levy receipts down 20%.

The economic consequences are dire. UK energy prices have skyrocketed to the highest levels in the developed world, crushing household budgets and rendering what remains of British manufacturing internationally uncompetitive. Industrial production is shrinking as energy-intensive sectors collapse or relocate to jurisdictions with stable, affordable power. The budget deficit is exploding under the weight of these policy choices—declining tax revenues from the North Sea combine with surging costs of energy subsidies and industrial support to create a fiscal black hole that the government is desperately trying to fill through tax increases rather than policy correction. Meanwhile, energy demand is weakening—not through efficiency gains but through economic contraction, exposing the fundamental relationship between energy availability and economic vitality. An economy is, at its core, an energy conversion system; when energy becomes scarce and expensive, economic activity necessarily contracts.

Figure 3 - via RH NUTALL (August 1, 2025)

Outlook

The zero-exploration outcome of 2025 represents a structural inflection point with cascading consequences extending beyond immediate production impacts. Without new field discoveries entering the development pipeline, the UK Continental Shelf's 3.3 billion barrels of proven and probable reserves will deplete faster than replacement rates, while Norway continues adding discovered resources through active exploration. The UK forecast of 180 field closures by 2030 assumes exploration success that is now absent, suggesting actual production decline will exceed current projections of 33.2 mtoe by 2030.

Three critical trajectories emerge from this policy-induced divergence.

First, UK import dependency will likely reach 80% by 2030, exposing the economy to greater geopolitical risk and foreign exchange pressures while simultaneously gutting domestic industrial capacity through unaffordable energy costs. Norway's continued exploration and new field developments, by contrast, position it to maintain stable production of 4+ million boepd through 2030 and remain Europe's largest energy exporter, with petroleum revenues continuing to fund the world's largest sovereign wealth fund.

Second, the UK North Sea supply chain faces existential threats—without exploration activity sustaining engineering, drilling, and service companies, the infrastructure required to extract remaining reserves becomes economically unviable, creating a "stranded asset" scenario. Norway's record $27 billion investment in 2025 demonstrates how supportive policy sustains industrial capability and technical expertise.

Third, the UK tax revenue gap widens further, with Treasury receipts potentially falling below £2 billion annually by 2030, while Norway's petroleum sector continues contributing approximately 20% of GDP and government revenues.

The Starmer Government's response—pursuing broader tax increases (contrary to electoral promises) across wealth and income while maintaining the punitive 78% Energy Profits Levy through 2030 in the November 2025 Budget—represents an attempt to extract revenue from a shrinking base rather than restore the conditions for growth, virtually guaranteeing accelerated decline.

Figure 4 - Multiple sources (see closing note)

Strategic Implications

The UK-Norway divergence provides empirical evidence that North Sea production decline rates are not purely geological constraints but are significantly influenced by fiscal and regulatory policy choices. Both countries share similar offshore geology, operational challenges, and technical expertise, yet Norway's 40 exploration wells versus the UK's zero in 2025 demonstrates how policy determines investment allocation. The UK's exploration freeze represents a strategic choice that is accelerating domestic production decline rather than managing the energy transition through continued investment in existing resources while developing alternatives.

Long-term implications for UK energy security, industrial capability, and economic sovereignty extend well beyond the 2030 horizon, particularly as Norway demonstrates that North Sea resources remain commercially viable under supportive policy frameworks. The economic pain is already manifest: the highest energy prices in the developed world, a shrinking industrial sector, exploding fiscal deficits, and weakening demand that signals deeper economic malaise. Energy is the foundation of economic activity; the UK is discovering that no amount of fiscal maneuvering can compensate for deliberate policy-driven energy scarcity.

Sources: This intelligence insight was developed through comprehensive analysis of authoritative industry, government, and research sources spanning UK and Norwegian North Sea operations. Primary data sources include the UK Government's Energy Trends September 2025 report and UK Energy in Brief 2025, which provided detailed production and import statistics, alongside the North Sea Transition Authority's reserves and production projections database. Norwegian data was sourced from the Norwegian Offshore Directorate's production figures and exploration statistics, supplemented by Norskpetroleum.no economic contribution data and Norway's sovereign wealth fund financial reports. Industry analysis drew heavily from Westwood Global Energy's 2025 UK-Norway exploration outlook survey, Offshore Energies UK's Business Outlook 2025, TMHCC's UK Energy Sector Report, and Discovery Alert's comparative analysis of North Sea investment strategies. The UK Department for Energy Security and Net Zero's November 2025 North Sea Strategy provided policy context, while the Society of Petroleum Engineers' historical analysis offered essential background on synchronized decline patterns. Financial and trade data came from RSM UK's oil and gas revenue analysis, official UK government statistics on import dependency, and UK Autumn Budget 2024 documentation detailing tax policy changes. News coverage from The Telegraph, BBC, France 24, and OilPrice.com documented the November 2025 policy developments and comparative UK-Norway energy market dynamics, while Energy News Beat, Energy Intelligence, and other industry publications tracked Norway's production growth trajectory, UK industrial sector contraction, and energy price differentials. Additional context on fiscal implications and budget deficit challenges was drawn from BBC coverage of the 2024 Autumn Budget and its impact on the oil and gas sector. All production volumes, import statistics, exploration well counts, fiscal data, and economic indicators were systematically cross-referenced across multiple independent sources to ensure accuracy and consistency, with particular attention paid to reconciling net import calculations with consumption and production balances, as well as validating claims regarding energy prices, industrial competitiveness, and budget impacts.