The 15-Year Nuclear Construction Gap: Strategic Realities Behind China's $2/Watt Achievement

- Technology Type

- Pressurized Water Reactor Nuclear Power Plants

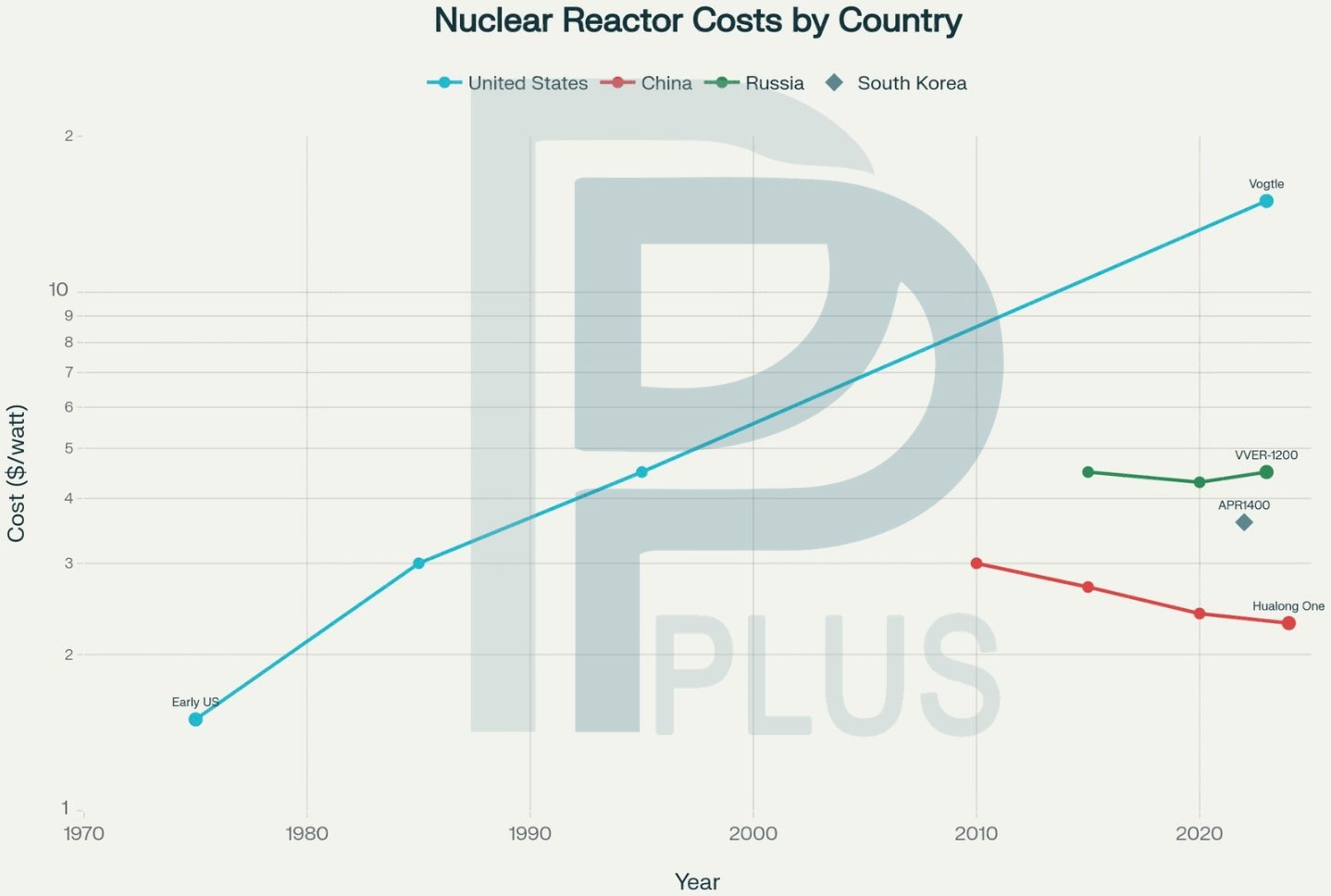

The nuclear construction cost divide between China's $2–3 per watt and America's $15 per watt represents far more than a simple price differential—it embodies a fundamental divergence in industrial strategy, supply chain maturity, and workforce continuity that has evolved over two decades. This analysis examines the strategic infrastructure buildout required to achieve competitive nuclear construction economics, drawing extensively from Chinese, Russian, and South Korean programs that successfully maintained industrial continuity. The evidence demonstrates that the path to $2–3 per watt construction costs requires 15–20 years of coordinated investment across supply chains, workforce development, and serial reactor construction—a timeline that challenges conventional assumptions about rapid nuclear deployment.

International comparison of nuclear reactor construction costs showing diverging trajectories between countries with

continuous programs (China, Russia, South Korea) and those with interrupted industrial capacity (United States)

The Anatomy of China's Nuclear Cost Advantage

Systematic Supply Chain Development (2000-2020)

China's achievement of $2.00–3.00 per watt construction costs for its Hualong One reactors did not emerge from superior technology alone, but rather from two decades of deliberate industrial policy aimed at creating complete domestic nuclear manufacturing capability. The program mobilized approximately 6,000 supplier enterprises and 5,400 equipment manufacturers to create an integrated supply chain capable of producing nuclear-grade components at scale. This localization strategy reduced China's dependence on foreign suppliers while enabling the cost efficiencies that come from domestic production and shortened logistics chains.

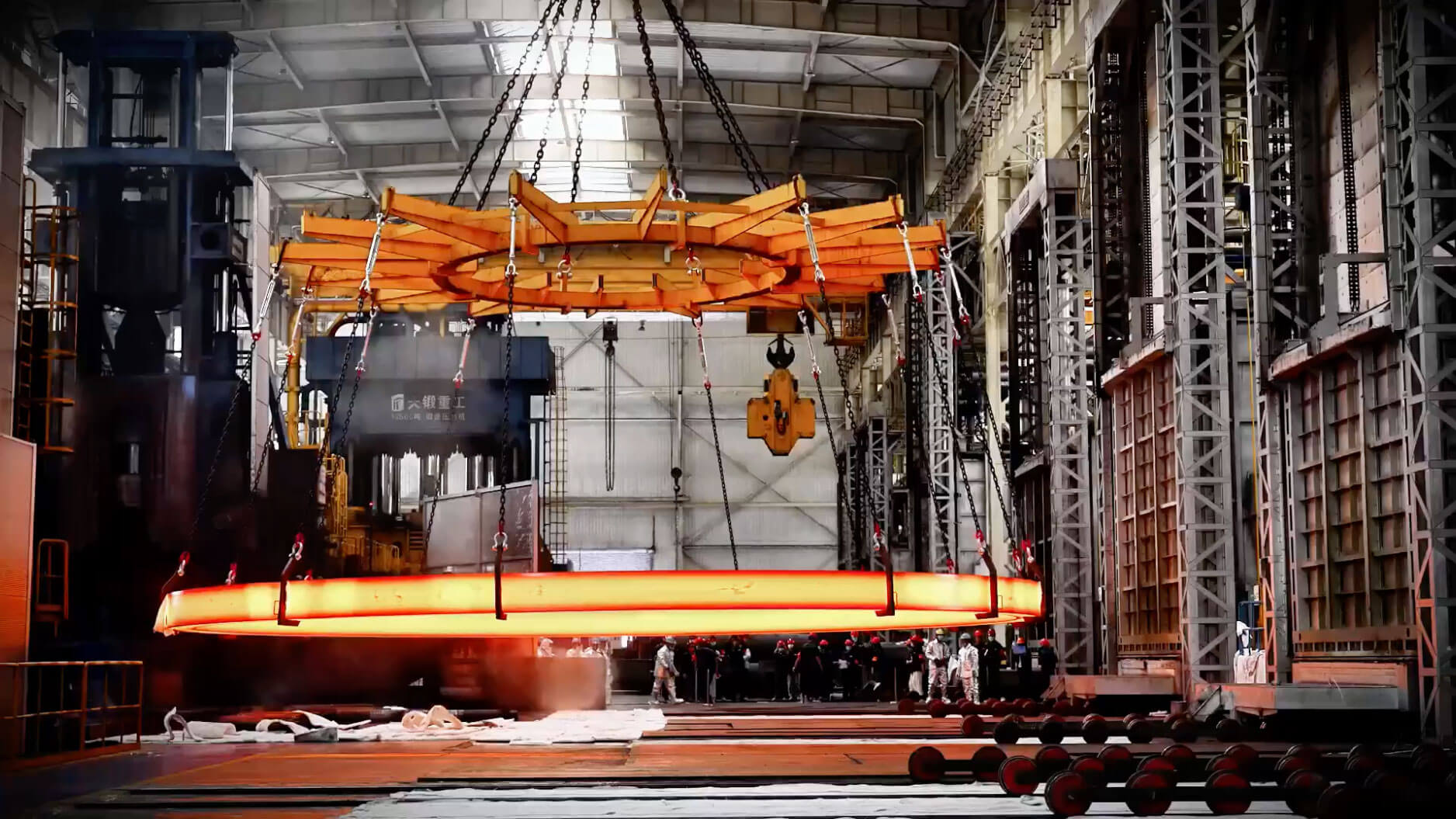

The scale of this supply chain development becomes apparent when examining specific capabilities. China First Heavy Industries (CFHI) and Shanghai Electric Corporation together operate multiple 12,000–17,000 tonne forging presses capable of producing reactor pressure vessels—the massive steel containers that house nuclear fuel and must withstand extreme temperatures and pressures. These facilities now produce an estimated 15–20 reactor pressure vessel sets annually, compared to zero domestic large-forging capacity in the United States for modern Generation III+ reactors. The establishment of this forging capacity alone required investments estimated at $50–75 billion and took approximately a decade to reach full operational capability.

150-tonne, 15.6-meter diameter stainless steel ring to play the supporting function in a nuclear reactor vessel

to withstand pressure up to 7,000 tonnes | Credit: Shandong Iraeta Heavy Industry Co Ltd

Beyond heavy forgings, China achieved complete domestic production of essential nuclear equipment including steam generators, pressurizers, reactor coolant pumps, and control rod drive mechanisms. This vertical integration eliminated the supply bottlenecks that plague programs dependent on a handful of global suppliers. When construction of Hualong One reactors accelerated after 2015, the domestic supply chain could respond to increased demand without the price escalation seen in markets with limited manufacturing capacity.

Financial Architecture and State Support

The financial structure supporting Chinese nuclear construction provides advantages that extend far beyond simple subsidies. State-owned enterprises like China National Nuclear Corporation (CNNC) and China General Nuclear (CGN) access financing with debt ratios of 70–80% at interest rates between 1.4% and 4%—substantially below the 7–9% weighted average cost of capital typical for U.S. nuclear projects. This differential in financing costs has profound implications: financing typically accounts for only around 15–20% of total project cost in China, versus 30–50% or more in higher-interest-rate environments. The state banking system's willingness to provide long-term, low-interest loans specifically for nuclear projects creates a financing environment that de-risks investment and enables rational long-term planning—advantages largely unavailable to private-sector nuclear developers in liberalized electricity markets.

This financial architecture also facilitates export competitiveness. Chinese state-owned enterprises can offer turnkey nuclear packages to Belt and Road Initiative countries with financing covering 80–85% of project costs on favorable terms, creating an integrated offering that combines reactor technology, engineering services, fuel supply, and project finance in a single package. This comprehensive approach positions China to capture an estimated 20–30% of the global nuclear export market, potentially constructing 30 reactors in approximately 40 countries by 2030.

The Learning Curve in Action: Hualong One Standardization

The Hualong One reactor design exemplifies how standardization drives learning curve benefits. Developed by CNNC with input from 75 domestic universities, research institutes, and equipment manufacturers, the design synthesized three decades of Chinese nuclear experience into a standardized third-generation pressurized water reactor with 1,000 MWe capacity. The first demonstration unit at Fuqing-5 achieved initial criticality in October 2020 after 68.7 months of construction—making it the only third-generation reactor globally delivered on its original schedule.

Aerial photo taken on Jan 27, 2021 shows the exterior view of nuclear power units of the

China National Nuclear Corporation (CNNC) in Fuqing, Southeast China's Fujian province. [Photo/Xinhua]

More significantly, subsequent Hualong One units demonstrated dramatic learning effects. Construction timelines compressed to 56–60 months for later units as workers gained experience, suppliers optimized component production, and project managers refined construction sequencing. As of 2025, 41 Hualong One units are approved, under construction, or operating, providing the serial production volume necessary to achieve and maintain cost discipline. This standardization extends deep into components and procedures, turning reactor construction into a repeatable industrial process rather than a series of unique mega-projects.

The economic impact appears clearly in cost trends. Chinese nuclear construction costs declined sharply during the 2000s as domestic supply chains matured and the workforce gained experience, then stabilized through the 2010s even as more advanced designs were introduced. This stands in stark contrast to the "negative learning" observed in France and the United States, where costs escalated despite accumulated experience—a phenomenon attributable to design changes, regulatory instability, and workforce discontinuity rather than any inherent characteristic of nuclear technology.

The Vogtle Experience: Quantifying the Cost of Industrial Discontinuity

Unprecedented Cost Escalation and Timeline Expansion

Plant Vogtle Units 3 and 4 in Georgia stand as the definitive case study in what happens when nuclear construction resumes after prolonged industrial dormancy. Originally approved in 2009 with an estimated cost of $14 billion and expected completion in 2016–2017, the project ultimately consumed approximately $36.8 billion and required 14–15 years to complete, with Unit 3 entering commercial operation in July 2023 and Unit 4 in April 2024. This represents a construction cost of approximately $15 per watt—five to seven times higher than contemporary Chinese reactor construction and more than triple South Korean costs.

Georgia Power Company has repeatedly inaccurately estimated costs for Plant Vogtle units 3 & 4

(Photo: Construction site as of Dec 2018)

The scale of cost overruns at Vogtle cannot be attributed to a single factor but rather reflects the compounding effects of supply chain gaps, workforce shortages, and the "first-of-a-kind" penalties inherent in deploying a new reactor design (Westinghouse AP1000) in a market that had not completed a new nuclear unit since Watts Bar 1 in 1996. Georgia Public Service Commission monitors documented that Southern Company provided "materially inaccurate cost estimates for at least ten years," with remaining costs consistently increasing even as billions were spent—a pattern suggesting fundamental inability to forecast completion requirements in an environment lacking recent experience.

Specific technical challenges illustrate the supply chain deficiencies. The AP1000 reactor pressure vessel could only be manufactured by a handful of global suppliers, primarily Japan Steel Works (JSW) and South Korea's Doosan Heavy Industries, as no U.S. facility possessed adequate heavy forging capacity for the 600-tonne steel ingots required. Similarly, critical components required nuclear-grade materials and precision manufacturing capabilities that had largely disappeared from the domestic industrial base during the 30-year construction hiatus.

The First-of-a-Kind Penalty and Design Instability

Vogtle suffered acutely from incomplete design maturity at construction start—a problem that plagued contemporary European Pressurized Reactor (EPR) projects in France and Finland as well. The project ultimately required more than 7,000 design changes during construction, with some modifications necessitating demolition and reconstruction of completed sections. This design instability extended construction timelines and created cascading delays as subsequent work could not proceed until modified designs were approved and implemented.

Comparatively, the only other major U.S. nuclear project begun this century—the V.C. Summer Nuclear Station in South Carolina—was abandoned in 2017 after cost estimates ballooned from $11.5 billion to $25.7 billion, demonstrating that Vogtle's struggles were not unique but rather symptomatic of systemic capacity deficits in the U.S. nuclear construction sector.

Workforce and Regulatory Challenges

The workforce challenges at Vogtle extended beyond simple labor shortages to encompass the loss of specialized nuclear construction expertise. Nuclear plant construction demands exceptionally specialized skills: welders must be certified for nuclear-grade work with testing requirements far exceeding conventional construction; quality assurance inspectors require training that can take up to four years; and project managers need experience with the unique regulatory and technical demands of nuclear projects. After a 30-year gap, this expertise had largely retired or transitioned to other industries.

Russia's VVER Strategy: Vertically Integrated Export Model

Rosatom's Global Market Dominance

Russia's state nuclear corporation Rosatom has achieved remarkable export success, controlling approximately 70% of the global nuclear reactor export market with 34 reactors under contract in 11 countries including Bangladesh, China, Egypt, Hungary, India, Kazakhstan, and Turkey. This dominance stems from a comprehensive "turnkey" approach that bundles reactor technology, engineering, construction, fuel supply, financing, and operational training into integrated packages backed by Russian government export credit agencies.

The VVER-1200, Rosatom's flagship Generation III+ pressurized water reactor design, demonstrates mature standardization with construction costs estimated at $4.0–5.5 billion per 1,200 MWe unit, equating to approximately $4.0–5.0 per watt—significantly above Chinese costs but well below Western projects. Kazakhstan's recently contracted two-unit VVER-1200 project carries an estimated timeline of 11 years from contract signing to commercial operation, with completion targeted for 2035–2036. While this represents longer timelines than Chinese projects, Rosatom's track record shows more consistent delivery than Western competitors.

VVER-1200 Reactors: Safe, Reliable, Efficient | Credit: Rosatom Newsletter (Sep 2025)

Financial Leverage and Strategic Implications

Rosatom's export competitiveness derives substantially from financing arrangements unavailable to commercial competitors. Russian state export credit agencies can provide loans covering up to 100% of project costs, with terms extending 20 years and grace periods of 7–8 years—allowing client countries to defer payments until reactors generate revenue. This financing transforms nuclear projects from exercises in national capital mobilization into manageable debt obligations secured by future electricity sales.

These arrangements create long-term dependencies through fuel contracts, operational support, and technology lock-in, giving Russia durable political leverage over client countries for the 60-year life of each plant.

Rosatom's portfolio of international orders totals approximately $200 billion over the next 10 years, with annual exports exceeding $10 billion. This orderbook provides the sustained demand necessary to maintain specialized manufacturing capabilities, train new cohorts of nuclear workers, and achieve incremental improvements in construction efficiency—advantages that compound over multiple projects.

South Korea's APR1400: Learning Curve Success and Policy Disruption

Methodical Capacity Development

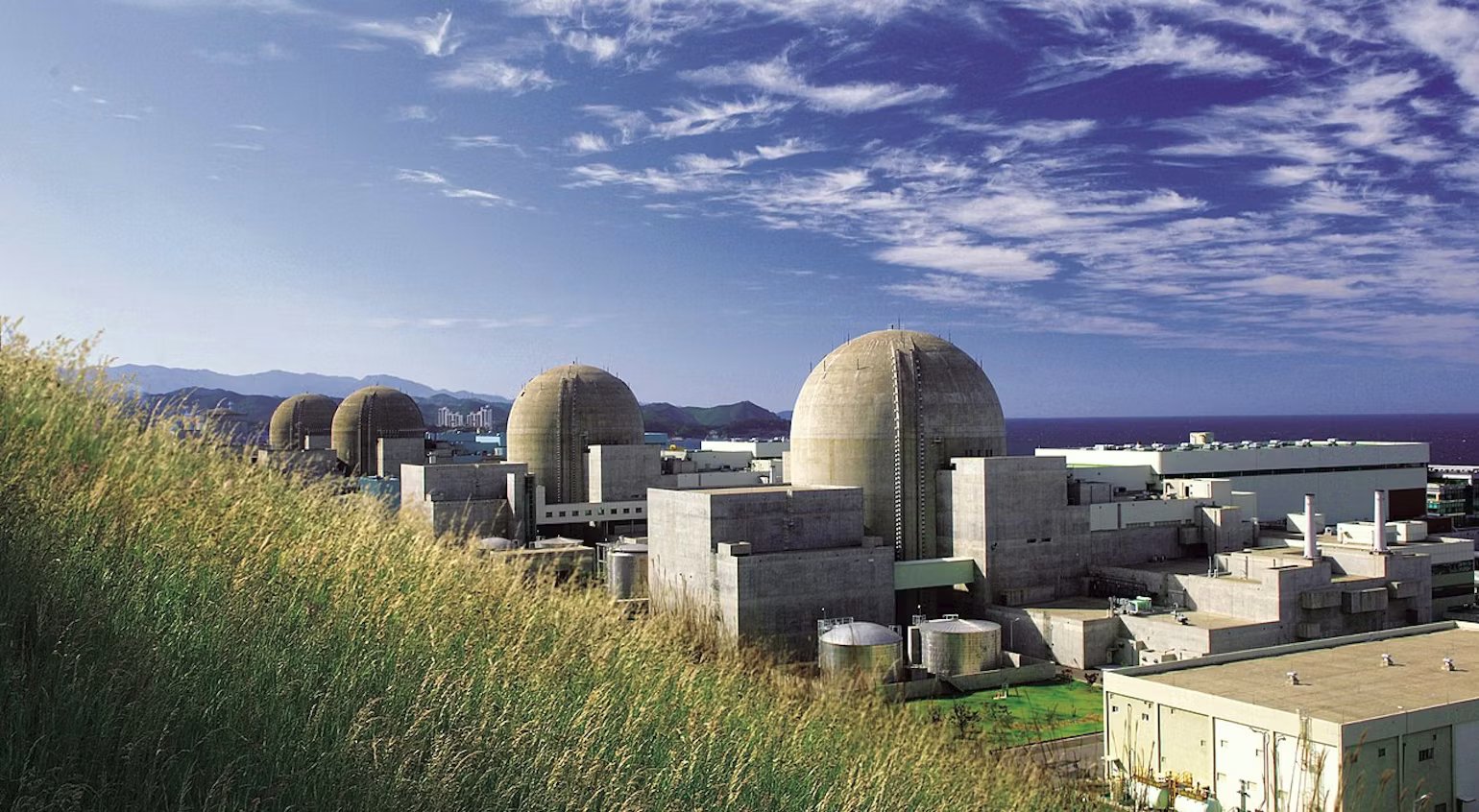

South Korea's nuclear program demonstrates how sustained commitment to standardized designs and domestic capability development can achieve competitive construction economics. The Advanced Power Reactor 1400 (APR1400), a 1,400 MWe Generation III+ pressurized water reactor, emerged from decades of progressive localization that began with technology transfer agreements in the 1970s and evolved through the OPR1000 intermediate design before reaching the fully indigenous APR1400.

The Barakah Nuclear Energy Plant in the United Arab Emirates showcases South Korean execution capability. The four-unit project, contracted at approximately $20 billion for 5,600 MWe total capacity ($3.6 per watt), achieved sequential completion from 2021–2024 at roughly one-year intervals—demonstrating the learning curve benefits when the same construction teams move directly from one unit to the next. This consistent performance earned South Korea regulatory certification in both Europe and the United States, validating the APR1400's technical excellence and safety features.

South Korea has approved the completion of two APR1400 nuclear plants at Shin-Hanul in the east of the country.

Photo: Courtesy of IAEA | Credit: NUCNET (Feb 21, 2025)

Doosan Heavy Industries, the primary equipment supplier, invested heavily in heavy forging capacity including 13,000-tonne and 17,000-tonne forging presses capable of producing reactor pressure vessels and other critical components. This vertical integration, combined with established supply chains developed over 40+ years of continuous construction, positioned South Korea to compete globally on both cost and reliability.

Vulnerability to Policy Shifts

Despite technical success, South Korea's nuclear program demonstrates vulnerability to political changes. Following the 2017 election of President Moon Jae-in, who campaigned on a nuclear phase-out platform, new reactor construction slowed substantially. The Shin-Hanul units faced construction suspensions and delays as policy uncertainty disrupted planning and investment. This policy instability, even in a country with proven nuclear capabilities, illustrates how political risk can undermine industrial continuity and squander accumulated expertise.

The workforce and supply chain impacts of such disruptions accumulate slowly but prove difficult to reverse. When construction volumes decline, specialized suppliers lose economies of scale, skilled workers transition to other industries, and engineering firms refocus on markets with more certain demand. Restarting a paused program then requires rebuilding capabilities at costs far exceeding the savings from the pause.

The French Nuclear Paradox: Volume Without Learning

The Messmer Plan Achievement and Its Erosion

France's nuclear program of the 1970s–1980s stands as one of history's most ambitious energy infrastructure buildouts, with 56 reactors of 900–1,450 MWe capacity constructed in approximately 15 years. This achievement, driven by Prime Minister Pierre Messmer's 1974 energy independence plan, established France as a global nuclear leader generating over 70% of electricity from atomic energy.

However, contrary to widespread assumptions, French nuclear construction exhibited "negative learning"—costs increased rather than decreased as cumulative experience accumulated. Arnulf Grubler's definitive 2010 analysis of French reactor costs documented real-term construction cost escalation throughout the program despite the high degree of standardization around Framatome PWR designs. This paradoxical outcome stemmed from progressive regulatory tightening and design changes that repeatedly modified plants while they were still being built.

Map of Nuclear Energy in France

Credit: Eric Gaba (Sting - fr:Sting), CC BY-SA 2.5, via Wikimedia Commons

The average construction time for French reactors during this period remained approximately 2.6 years faster than contemporary U.S. projects—a significant advantage attributable to regulatory stability, centralized decision-making through state-owned Électricité de France (EDF), and workforce continuity. Yet this speed advantage could not offset the underlying cost escalation driven by evolving requirements and the inherent complexity of each generation of larger reactors.

The Flamanville's Costly Lessons and the EPR2 Gamble

The gap between completion of Civaux-2 in 1999 and the start of Flamanville-3 construction in 2007 proved extraordinarily costly for French nuclear capabilities. The new European Pressurized Reactor (EPR) design, intended to represent the pinnacle of nuclear technology with enhanced safety features and 1,650 MWe capacity, instead became emblematic of cost overrun and delay. Originally budgeted at €3.3 billion with a 54-month construction timeline, Flamanville-3 ballooned to €23.7 billion (a 600% cost increase) and rtook 17 years from construction start (2007) to grid connection (December 2024)—a delay of 12 years beyond the original 2012 target.

The Flamanville EPR, France's most powerful nuclear reactor, is finally connected to the electricity grid

Credit: Le Figaro (Dec 22, 2024)

Multiple factors drove these massive cost and schedule overruns. The EPR's unprecedented complexity—with thousands of specialized welds, advanced digital control systems, and massive reactor pressure vessel requiring precision manufacturing at the limits of supplier capability—exceeded available expertise after the 1999–2007 construction gap. The project began before design completion, resulting in over 7,000 design changes during construction and requiring some sections to be demolished and rebuilt. Quality control failures plagued critical components: the reactor pressure vessel had carbon concentration abnormalities, the containment dome developed cracks, and instrumentation systems required extensive rework.

Organizational dysfunction compounded technical challenges. Rivalry between EDF and construction manager Areva created coordination failures, while regulatory authorities lacked clear processes for managing such a complex project after years without new construction. The workforce, trained on simpler Generation II designs, struggled with EPR requirements.

France's response—the EPR2 program aiming to build six reactors using lessons from Flamanville—represents a calculated gamble. The EPR2 promises simplified, more buildable design; improved project management; reconstituted workforce through intensive training programs; and reorganized governance placing EDF firmly in charge. Yet design optimization continues, and delays in previous EPR projects in China and Finland add complexity to incorporating lessons learned. Whether EPR2 can achieve its target costs of $4.0–6.0 per watt and construction times of 84–120 months remains unproven.

The U.S. Path Forward: Confronting a 15-20 Year Industrial Rebuild

Supply Chain Reconstruction Requirements

Restarting American nuclear construction at competitive costs requires addressing severe supply chain deficiencies that developed during three decades of dormancy. The United States currently possesses zero domestic capacity for manufacturing modern Generation III+ reactor pressure vessels, as existing forging presses max out at 10,000 tonnes—inadequate for the 14,000–17,000 tonne capacity required for AP1000 or similar large forgings. Rebuilding this capability demands investments estimated at $80–120 billion in heavy manufacturing infrastructure including forging presses, machining facilities, and the integrated steel mills capable of producing 600-tonne hot ingots.

Rebuilding this capability demands tens of billions of dollars of investment in heavy forging, machining, steelmaking, and specialized component manufacturing. Many suppliers exited the sector during the hiatus, and attracting new entrants will require credible demand for a fleet of at least 10–20 reactors.

The timeline for supply chain development cannot be compressed significantly. Establishing forging capacity requires 3–4 years for facility construction, equipment installation, and qualification testing, then additional time to train workers and refine processes to meet nuclear quality requirements. Component manufacturers need similar timescales to develop nuclear-grade production capabilities and obtain ASME certifications. Consequently, even with immediate commitment and funding, achieving mature domestic supply chains requires approximately 10 years—a reality that challenges political expectations of rapid deployment.

Workforce Development at Scale

The workforce challenge dwarfs supply chain reconstruction in both magnitude and complexity. Expanding U.S. nuclear capacity from 100 GW to 400 GW by 2050—the scale necessary to materially address climate and energy security goals—requires 375,000 additional workers according to Department of Energy estimates. This breaks down to approximately 100,000 for operations and 275,000 for construction and manufacturing—more than quintupling the current nuclear workforce of 68,000.

Nuclear workforce development faces unique challenges. Training timelines extend up to four years for highly specialized positions including nuclear welders, quality assurance inspectors, and reactor operators. Certification requirements demand intensive screening including background checks, psychological evaluations, and ongoing testing. The specialized nature of nuclear work means that adjacent industries—while potentially sources of transferable skills—require significant "nuclearization" training before workers can contribute effectively.

The age profile of the existing workforce compounds these challenges. With 60% of nuclear workers aged 30–54, substantial retirements will occur over the next decade, requiring replacement even to maintain current capacity. The broader labor market context—with 600,000 unfilled construction and manufacturing positions nationwide—means nuclear projects must compete aggressively for talent in tight labor markets.

Meeting this need will require coordinated action across states, federal agencies, universities, and industry—expanding vocational training, nuclear engineering programs, and apprenticeships, and creating clear long-term career paths. Even with strong policy support, building training capacity and experience pipelines is a 10–15-year task.

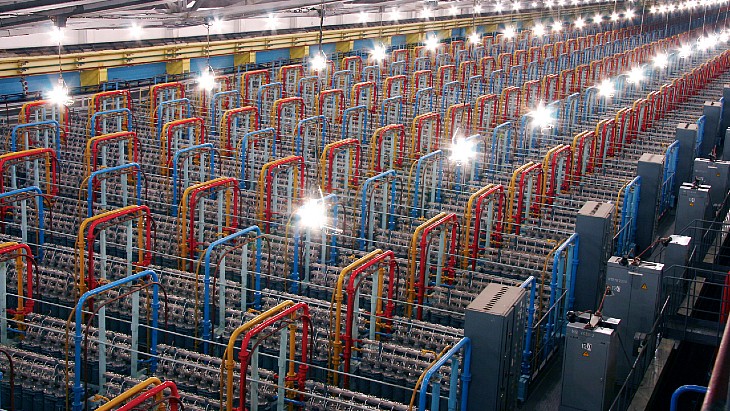

High-Assay Low-Enriched Uranium (HALEU) Bottleneck

Advanced reactor designs—including many small modular reactors (SMRs) and Generation IV concepts—require high-assay low-enriched uranium (HALEU) enriched between 10% and 20% U-235, compared to the 3–5% enrichment used by the current reactor fleet. The United States possesses minimal HALEU production capability: Centrus Energy operates a 16-machine demonstration cascade in Piketon, Ohio producing approximately 900 kg per year, far below the estimated 2,000 tonnes needed by 2035.

New gas centrifuge for separating uranium isotopes undergoing pilot industrial operation

Photo: TVEL | Credit: world nuclear news (Jul 21, 2025)

The Department of Energy aims to make 21 metric tons of HALEU available by June 2026 through down-blending of highly enriched uranium, providing a near-term stopgap. However, commercial-scale HALEU production requires 5–10 years to establish, with significant regulatory hurdles as uranium enriched above 10% must be handled in Category II facilities with more stringent security requirements. This timeline gap creates potential bottlenecks for advanced reactor deployment in the 2027–2032 timeframe even if reactor designs gain regulatory approval.

Recent DOE contracts with six enrichment companies—including both centrifuge operators (Centrus, Urenco) and emerging laser enrichment firms—aim to stimulate domestic capacity buildout. Yet achieving production at the required scale demands substantial capital investment estimated at $2–4 billion for facilities, plus 3–4 years for construction and commissioning according to DOE analysis.

Standardization Discipline and the Learning Curve

Perhaps the most critical challenge facing U.S. nuclear revival is organizational: maintaining disciplined standardization over 10–20 reactors to capture learning curve benefits. DOE analysis confirms that optimal nuclear economics require building 10–20 reactors sequentially using the same design, allowing supply chains to mature, workforces to gain proficiency, and construction processes to be refined. Yet American nuclear history demonstrates persistent temptation to customize designs for site-specific considerations, incorporate new safety features, or accommodate utility preferences—changes that fracture standardization and reset learning curves.

The challenge manifests in current reactor development. The Westinghouse AP1000, intended as a standard design, suffered from insufficient maturity at first deployment, leading to extensive field modifications. Multiple advanced reactor vendors now compete for attention—NuScale, TerraPower, X-energy, Kairos Power, and others—each with distinct designs and fuel requirements. While this diversity drives innovation, it fragments potential orderbook volume, preventing any single design from achieving the serial production necessary for learning curve economics.

China's Hualong One success demonstrates the alternative path: sustained commitment to a single design across 41 units, resisting modification pressure to capture learning benefits. South Korea's APR1400 program similarly maintained design discipline through multiple projects. France's attempt at standardization in the 1970s–1980s partially succeeded in achieving construction speed advantages but suffered from progressive design evolution that undermined cost learning.

For the United States to achieve competitive nuclear costs, policymakers and industry must accept that the first reactor may cost $10–15 per watt, but maintain standardization discipline so that reactor #15–20 can approach $3–4 per watt through accumulated learning. This requires political will to endure years of "why is nuclear still expensive?" headlines while the learning curve does its work—a challenge in democracies with short political cycles and extensive public scrutiny of nuclear projects.

Small Modular Reactors: Promise and Protracted Timelines

The Factory Production Premise

Small modular reactors represent a fundamentally different approach to nuclear deployment, promising to address many large reactor challenges through factory fabrication of standardized modules, shorter construction timelines, and reduced capital requirements. With capacities typically ranging from 50 to 300 MWe per module, SMRs could be manufactured in controlled factory environments then shipped to sites for assembly—potentially reducing on-site construction from 5–10 years to 24–36 months.

The economic logic centers on manufacturing learning curves rather than construction learning curves. Factory production could exploit economies of scale and achieve cost reductions through series production far more readily than site-built reactors. Smaller size reduces capital at risk and may facilitate financing, while modularity allows incremental capacity additions matching demand growth. Passive safety features potentially simplify licensing and reduce redundant systems, further controlling costs.

More than 150 SMR designs are in various stages of development globally, representing diverse technologies including light water reactors, high-temperature gas reactors, molten salt systems, and sodium-cooled fast reactors. The proliferation of concepts reflects intense competition to identify winning configurations and business models, with substantial private investment and government support fueling development.

Commercial Reality Check

Despite conceptual promise, SMR commercial deployment faces significant timeline delays. As of 2025, only two commercial SMRs operate globally—one in Russia (floating KLT-40S) and one in China (HTR-PM)—with three designs approved for construction by the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission but none yet operating. The most advanced U.S. design, NuScale's 77 MWe reactor, saw its flagship Carbon Free Power Project (formerly UAMPS) canceled in 2023 due to escalating costs, demonstrating that early SMR economics remain challenging.

Rosatom was the first nuclear vendor to bring its own SMR design to life when in December 2019 it connected floating power unit

Akademik Lomonosov to the grid in Russia’s northernmost town of Pevek | Credit: Rosatom Newsletter (Feb 2023)

Regulatory timelines compound delays. While the ADVANCE Act of 2024 introduced reforms including 50% fee reductions for SMR applications and expedited pathways for demonstration reactors, the fundamental generic design assessment process still requires 3–5 years even with streamlined procedures. Manufacturing licenses—a new regulatory construct for factory-produced reactors—require additional review cycles. Consequently, even optimistic projections place widespread SMR availability in the mid-2030s at earliest.

The HALEU fuel requirement of many advanced SMR designs creates additional bottlenecks, as discussed previously. Without assured fuel supply, SMR deployment timelines remain uncertain regardless of reactor design maturity.

Implications for Near-Term Strategy

The SMR timeline reality suggests that relying on small modular reactors to rapidly address near-term energy needs represents misplaced optimism. While SMRs may eventually contribute meaningfully to decarbonization—potentially capturing niche applications in remote locations, industrial facilities, and as coal plant replacements—they cannot substitute for immediate action on proven large reactor technologies for projects targeting the 2030–2040 timeframe.

This does not argue against SMR development, which could prove transformative if manufacturing economics materialize. Rather, it counsels realistic assessment that SMRs exist in a different timeline than near-term deployment needs. Countries and utilities seeking to expand nuclear capacity in the next 10–15 years must work with established large reactor designs where learning curves, supply chains, and construction experience already exist—even if that means accepting higher first-unit costs to begin accumulating serial production experience.

Strategic Implications and Policy Recommendations

The Irreducible Timeline Reality

The evidence across multiple national programs converges on an uncomfortable truth: achieving competitive nuclear construction costs of $2–4 per watt requires 15–20 years of systematic investment in supply chains, workforce development, and serial reactor construction. This timeline cannot be compressed significantly through policy reforms, regulatory streamlining, or technological innovation alone—though all remain valuable—because it fundamentally reflects the time required to develop specialized manufacturing capabilities, train expert workforces, and accumulate learning curve benefits.

Russia's program maintained continuity from the Soviet era through the present, avoiding the capacity gaps that plague Western programs. Even with this continuity, export VVER-1200 projects require 11-year timelines and cost $4–5 per watt—above Chinese levels but benefiting from decades of accumulated expertise.

Alternative Paths and Their Trade-offs

Facing 15–20 year domestic buildout timelines, the United States confronts strategic choices with distinct implications. One path pursues full domestic capability reconstruction despite extended timelines, accepting that first reactors will cost $10–15 per watt but maintaining standardization discipline through 15–20 units to reach competitive $3–4 per watt costs by the late 2040s. This approach maximizes long-term strategic autonomy and positions the U.S. to compete in future global nuclear markets, but requires sustained political commitment and several hundred billion dollars of investment over 25+ years.

An alternative path leverages international partnerships to compress timelines. South Korea's APR1400 offers proven technology at $3–4 per watt with 5–7 year construction timelines, regulatory certifications in the U.S. and Europe, and a supplier base (Doosan Heavy Industries) with adequate capacity. While depending on foreign technology contradicts conventional energy security narratives, it could enable deployment of 10+ reactors in the 2030–2040 timeframe while domestic capabilities develop in parallel—potentially through technology transfer and licensed production agreements that build U.S. manufacturing capacity under foreign technical guidance.

A third path focuses U.S. development efforts on advanced reactor concepts and SMRs where American innovation may offer competitive advantages, conceding the large reactor market to established international suppliers. This specialization strategy could capture emerging market segments (distributed generation, industrial process heat, remote applications) where U.S. technology leadership remains viable, rather than competing in standardized large reactors where China, Russia, and South Korea possess entrenched advantages.

Each path involves trade-offs between timeline, cost, strategic autonomy, and technological positioning. The critical error would be assuming that any approach enables rapid, cost-competitive deployment without confronting the fundamental industrial development timelines that evidence demonstrates.

Financing Innovation and Risk Allocation

Beyond timelines and technical capacity, nuclear economics hinge critically on financing structures and risk allocation. China's $2–3 per watt costs depend substantially on 70–80% debt financing at 1.4–4% interest rates, with financing costs representing only 14–18% of total project investment. Comparatively, U.S. nuclear projects facing 7–9% weighted average cost of capital see financing consume 30–50% of total costs, overwhelming construction efficiency gains.

Policy innovation in financing could materially improve U.S. nuclear economics without requiring decades of industrial development. Options include:

-

Enhanced Loan Guarantees: Expanding the Department of Energy Loan Programs Office to offer loan guarantees covering 80–90% of project costs at rates approaching government borrowing costs (currently ~4–5%) rather than commercial project finance rates. This de-risks private investment and reduces financing burdens to levels more comparable with state-backed programs.

-

Investment Tax Credits: The Inflation Reduction Act introduced production tax credits for nuclear generation; extending investment tax credits to cover construction reduces upfront capital requirements. Milestone-based credit allocations could incentivize on-time, on-budget completion.

-

State-Level Clean Energy Standards: Enabling nuclear inclusion in clean energy mandates and providing preferential financing through state green banks or infrastructure programs. Several states (Pennsylvania, Virginia, others) have implemented nuclear support mechanisms that could be expanded.

-

Power Purchase Agreement Structures: Long-term contracts (20–30 years) with creditworthy offtakers (utilities, large industrial consumers, data centers) that provide revenue certainty justifying lower financing costs. Recent agreements between tech companies (Google, Microsoft, Amazon) and nuclear developers demonstrate market interest in this model.

These financing innovations could potentially reduce total project costs by 20–40% even without construction efficiency improvements, making U.S. nuclear more competitive during the industrial rebuild phase.

The Political Economy Challenge

The fundamental barrier to U.S. nuclear revival may be political rather than technical. Achieving competitive nuclear costs requires accepting that initial projects will be expensive while learning curves develop—enduring perhaps 10-15 years of cost overruns, delays, and negative press coverage until standardization and experience drive costs down. Democratic political systems with 2-4 year election cycles, extensive public scrutiny, and powerful anti-nuclear advocacy networks provide hostile environments for such long-term industrial strategies.

China's command economy, with centralized decision-making, state-owned enterprises, and multi-decade planning horizons, proves far more conducive to sustained nuclear buildout. Russia's state-directed approach offers similar advantages. Even France's nuclear success in the 1970s-1980s occurred under centralized state utility (EDF) direction with minimal public input into energy strategy.

Yet democratic governance need not preclude nuclear success. South Korea achieved its nuclear program within a democratic framework (post-1987), albeit with strong state direction and public acceptance of nuclear energy. The political challenge lies in building durable coalitions that support nuclear investment through multiple electoral cycles and inevitable project difficulties.

This requires reframing nuclear from a purely technical or economic question to a strategic imperative comparable to defense industrial base maintenance or critical infrastructure resilience. Just as the United States maintains defense manufacturing capabilities at costs exceeding foreign alternatives for strategic reasons, nuclear could be positioned as essential infrastructure requiring sustained investment regardless of near-term economic optimality. Climate imperatives, energy security concerns (particularly regarding data center and AI computational loads), and economic competitiveness arguments all potentially support such strategic framing.

Outlook: Racing to 2045, Not 2030

The $2 per watt nuclear construction costs achieved by China represent the outcome of systematic 20-year investments in industrial infrastructure, workforce development, and standardized design implementation that began around 2000 and matured in the 2020s. The pathway is well-documented: establish domestic supply chains including heavy forging capacity ($50-120 billion over 10 years), develop specialized workforce at scale (200,000-400,000 workers over 10-15 years), select and commit to standardized designs, then build 15-20 reactors sequentially to capture learning curve benefits ($200-400 billion in total reactor investments over 15-20 years).

For the United States, beginning this journey in 2025 means achieving competitive nuclear costs around 2040-2045 at earliest, assuming sustained commitment and optimized execution. Nations looking to China's $2/watt costs as evidence that nuclear can rapidly scale face the inconvenient reality that China itself required two decades to reach current performance—decades that cannot be skipped through policy innovation or regulatory reform alone.

This timeline reality does not argue against pursuing nuclear energy, which remains essential for deep decarbonization, energy security, and industrial competitiveness in an era of soaring electricity demand. Rather, it counsels realistic expectations and strategic patience. The first reactors will cost $10-15 per watt; political and financial structures must accommodate this reality while maintaining standardization discipline to capture learning benefits. Alternative approaches including international partnerships, advanced reactor specialization, and financing innovation merit serious consideration as complements to domestic capability development.

The question confronting policymakers is not whether to pursue competitive nuclear construction costs—which remains achievable and strategically valuable—but whether democratic political systems can sustain the 15-20 year investments required despite inevitable setbacks, cost overruns, and criticism that will emerge during the learning curve phase. China, Russia, and South Korea have demonstrated the pathway; Western nations must now determine if their political economies can follow it.

This analysis builds upon research from government agencies (U.S. DOE, EIA, CAEA, CNNC, IAEA, OECD-NEA), academic institutions (MIT, Johns Hopkins, Idaho National Laboratory, CNRS), nuclear industry organizations (World Nuclear Association, ANS, NEI), consulting firms (Deloitte, ITIF, T. Rowe Price, IEEFA), and international media sources including Bloomberg, Reuters, World Nuclear News, and specialized publications focused on nuclear energy economics and industrial policy.

#nuclearenergy #nuclearpowerplant #npp #bwr #phwr #pwr #boilingwaterreactor #pressurizedheavywaterreactor #pressurizedwaterreactor #smallmodularreactor #smr